Us Will Review All the Humanitarain Aid to South Sudan White House

Accessing Due south Sudan: Humanitarian Aid in a Time of Crisis

CSIS Briefs

November 27, 2018

The Result

Since gaining its independence from Sudan in 2011, Due south Sudan has struggled to fulfill the promise of a new nation, eventually descending into ceremonious war in late 2013. The land is at present bearing the devastating human and financial costs of a complex conflict with ever-changing armed and political actors. Assistance organizations face an array of humanitarian access constraints while working to address the acute needs of seven million people, roughly half of the state. Although there is cause for cautious optimism later a peace understanding was signed in September 2018, these humanitarian needs will only grow in the absence of sustainable peace and a political solution to the human-fabricated crunch in South Sudan.

Southward Sudan has received pregnant humanitarian aid from the U.s. and the international community for decades. Since 2011, total humanitarian funding surpassed $9.5 billion, most of which has been part of the coordinated South Sudan Humanitarian Response Programme (SSHRP).1The U.Southward. regime has provided almost $3 billion to the SSHRP, with even more than to evolution priorities.ii This aid has helped and continues to help millions: in 2017 alone, more than than 5 million people received nutrient assistance, almost three million people received emergency wellness kits, and nearly one 1000000 children and pregnant and lactating women were treated for malnutrition.three

Some hoped that peace and prosperity would follow years of devastating armed disharmonize. Such hopes were, however, curt-lived: Due south Sudan descended into ceremonious war in tardily 2013. Since and so, more than four one thousand thousand South Sudanese, or approximately 1 in 3 of its citizens, 85 per centum of whom are women and children, take been forced from home. The protracted crisis is farther complicated by domestic political actors who seem immune from or uninterested in the suffering of their people and regional diplomatic processes that often result in fleeting promises of reconciliation earlier retreat into armed conflict.iv This has led to a staggering number of South Sudanese caught in the cross fire. Of the 7 1000000 people currently in need of humanitarian aid, 5.3 meg are food insecure.fiveA recent written report showed that the disharmonize has led to almost 400,000 deaths since late 2013.half-dozen

With and so much need, the land relies heavily on external humanitarian funding, which should be credited for saving endless South Sudanese lives. All the same, the United nations estimates electric current needs at $one.seven billion, but half of which has been funded to appointment.sevenAt the same time, the Trump Administration initiated a comprehensive review of its help programs to Southward Sudan in May 2018. In its statement, the White Business firm said that while the The states remained "committed to saving lives, nosotros must too ensure our assistance does not contribute to or prolong the disharmonize, or facilitate predatory or corrupt behavior".8Ultimately, a cessation of hostilities, a more inclusive and reconciliatory political process that results in a functional government delivering services to citizens, and economic growth all are critical for South Sudan to one mean solar day sally from this night menses in its history. These goals accept proved elusive, primarily considering of armed disharmonize, and aid groups detect themselves dealing with predatory and frequently corrupt behavior that increases the human and fiscal costs of humanitarian access. Although similar or even more acute challenges may exist in other places (e.g., Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen), the constraints in Southward Sudan on aiding some of the most vulnerable people on the planet are no less formidable.

Figure 1: S Sudan Humanitarian Response Programme Funding

Inconsistent access in South Sudan is coupled with staggering homo costs: today more half of the state's population is in demand of life-saving humanitarian aid. Protracted and widespread conflict means that people throughout the country are suffering, stretching the chapters of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and offering opportunities for land and nonstate actors to manipulate assist for their own, primarily nonhumanitarian purposes. To deliver humanitarian help to vulnerable people, NGO workers must regularly navigate admission with myriad local actors, many of whom are armed. They have limited coin, food, supplies, and vehicles and thus see NGO-provided appurtenances as ripe for exploitation.

Thus, the homo costs of humanitarian access constraints are most astute for those who are unable to receive assistance. Merely the costs to the people delivering that aid are also loftier. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) counts 192 organizations currently responding to the crisis in South Sudan with emergency programs; more 100 aid workers from these and other organizations accept died since the near recent disharmonize erupted in 2013.9 In 2017, South Sudan was the most dangerous country for assistance workers, with l per centum more workers killed than in Syria and 612 aid workers forced to relocate due to ongoing conflict.10 Already in 2018, 36 assistance workers have been kidnapped, with a vast majority of those at risk working for national NGOs.11In response, many NGOs maintain security apparatuses that add to the already high financial costs of operating in Southward Sudan.

The financial and bureaucratic costs of delivering aid in Southward Sudan rank among the highest in the world.

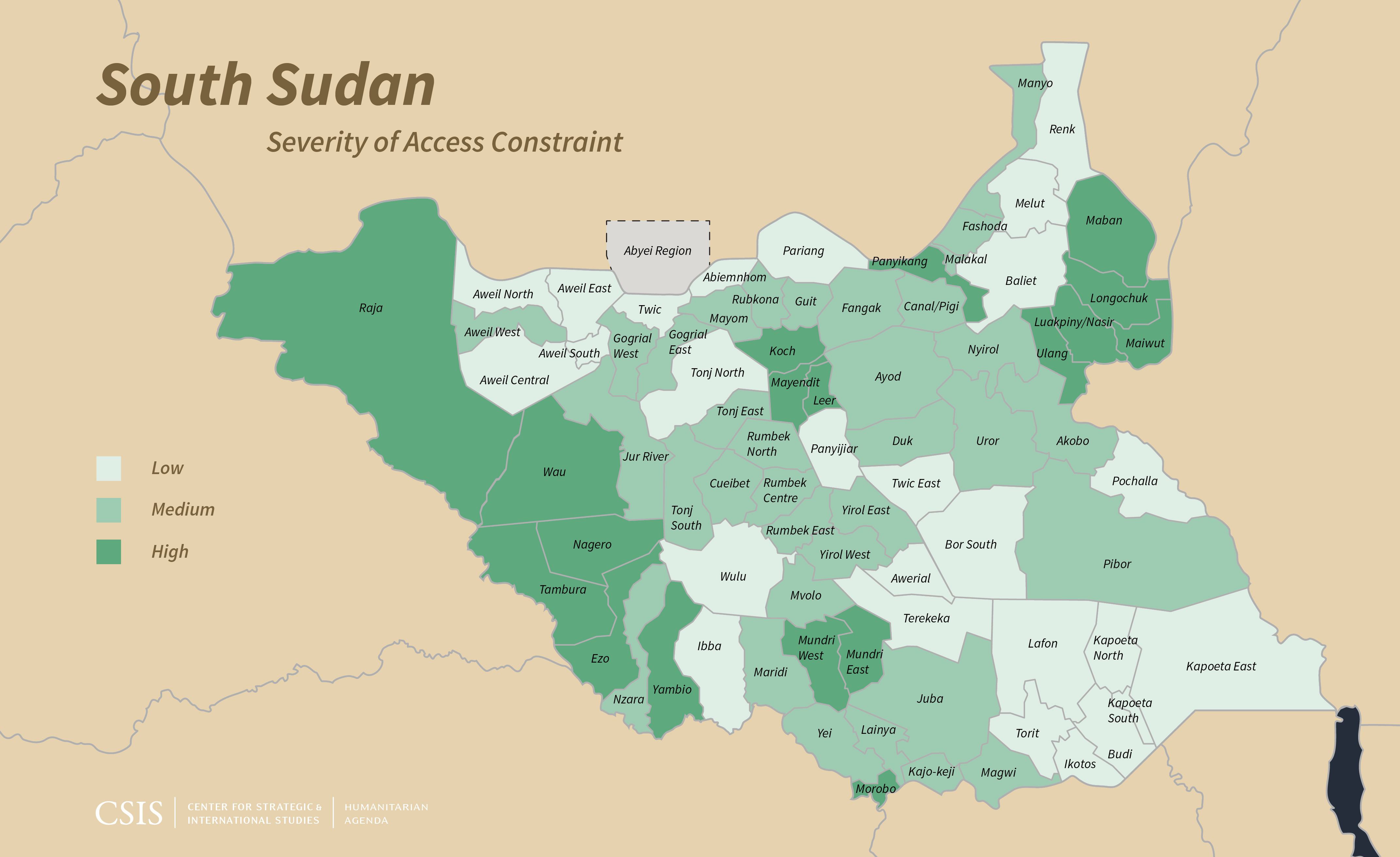

Source: UNOCHA, S Sudan: Humanitarian Access Severity Overview (September 2018)

Source: UNOCHA, S Sudan: Humanitarian Access Severity Overview (September 2018)

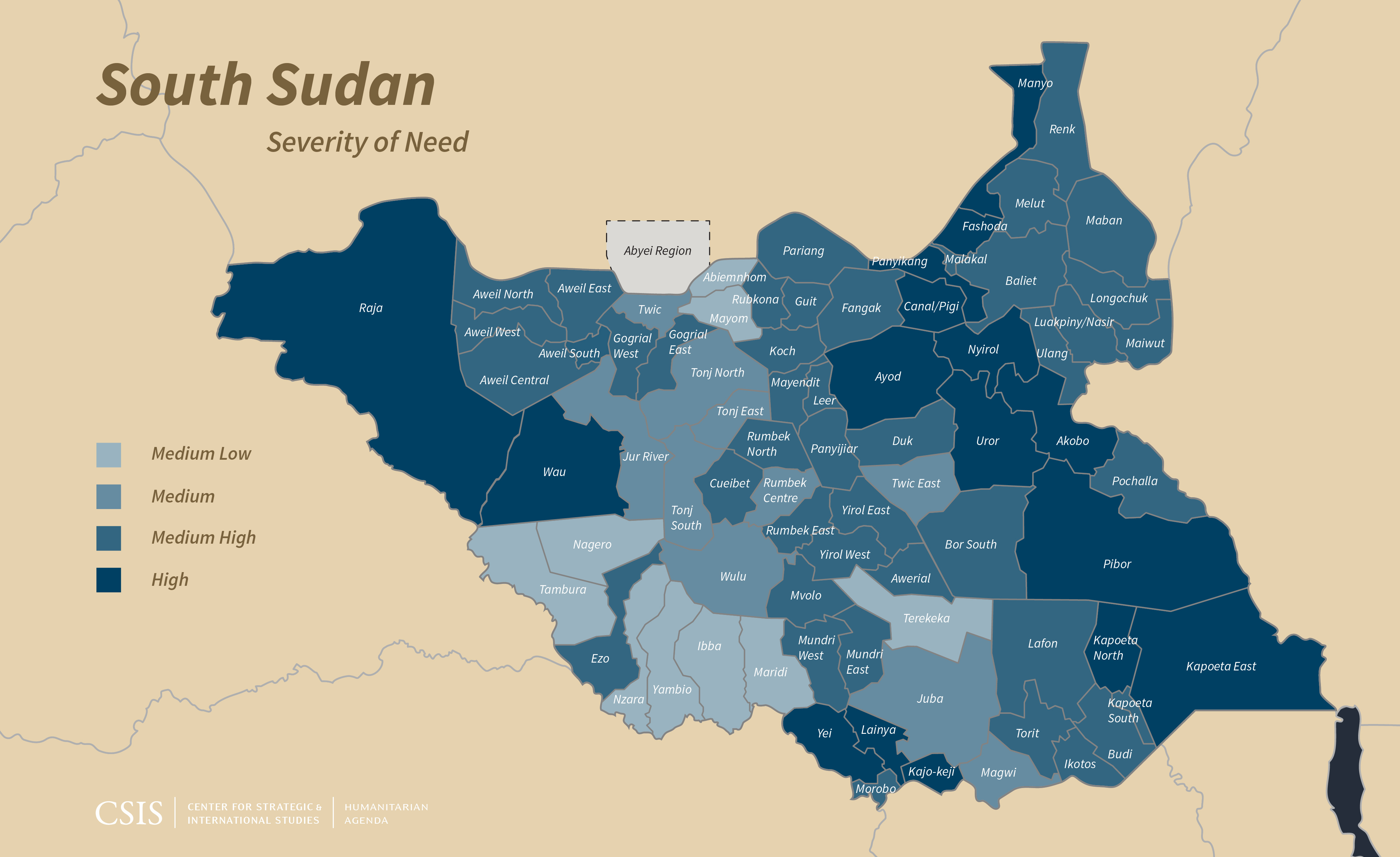

Source: UNOCHA, 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview

Source: UNOCHA, 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview

Of the 78 counties in South Sudan, 18 have loftier-level (where admission is extremely difficult or impossible) and 34 have medium-level (where information technology is regularly restricted) access constraints.12NGOs practice have some admission to all parts of the state, but it is intermittent, plush (in time and resources), and often comes at cracking physical take a chance to those delivering the aid. Myriad and ever-changing bureaucratic approval processes at the local, canton, state, and national levels mean that NGOs sometimes spend months securing the necessary permissions to operate. Some reports suggest that access is controlled by armed actors not only for economic gain, but also to cut off humanitarian assist to people and places deemed disloyal or in opposition. Every bit a result, some NGOs operate without official authorization, which puts them at gamble for legal reprisal, while others are forced to pay bribes or be barred from the country altogether—all at the expense of donors, S Sudanese government, and most importantly, the 7 million Due south Sudanese who are in need. In a state rife with tribal conflict, local NGOs often face additional access challenges (east.g., an system founded by someone of Nuer origin may have difficulty operating in a predominately Murle part of the country), though they are oft more risk tolerant and willing to operate in difficult locations to deliver humanitarian aid.13

Although many of South Sudan's access issues take political roots and solutions, these challenges are exacerbated by the fact that every bit much as lxx pct of the country is inaccessible by road during the rainy season, which typically lasts from June through September.fourteen Infrastructure, in full general, has been a significant access constraint—equally has the ubiquity of landmines and unexploded ordinance—in South Sudan for decades and continues to be one today.xvHowever, these constraints are more predictable and typically accept clearer solutions and thus could be addressed should the political and conflict-related access issues be resolved.

In addition, humanitarian actors face significant, unpredictable fiscal and bureaucratic costs that delay delivery of services and divert funds from aid recipients.16 One international NGO with an in-country staff of fewer than 200 people estimates that information technology spends approximately $350,000 per year in Due south Sudan on administrative taxes and fees.17These financial costs are primarily paid to official or quasi-official entities; NGOs also have to negotiate humanitarian access with at to the lowest degree 70 singled-out armed groups beyond the country, near of which need different fees or atmospheric condition earlier granting access.eighteenWith such a circuitous web of armed conflict, these actors tin can too change daily, invalidating previously negotiated access and starting the expensive, time-consuming, and dangerous process over again.

Additionally, humanitarian organizations have lost millions of dollars' worth of aid to looting, raids on compounds, theft, and other instances of criminal capture, not to mention the costs associated with regularly relocating or evacuating staff members considering of whatsoever one of these factors.19NGO compounds exterior urban areas are particularly susceptible to criminal capture when, due to insecurity or other factors, staff members are forced to evacuate. Although some of these costs are the results of an always-deteriorating economy with limited opportunities for productive income generation, at that place have been anecdotal reports of increased animosity towards international actors who—paradoxically and particularly in the absenteeism of a functioning regime—are oftentimes seen as the just ones with the power to alleviate suffering, not independent and thus politically motivated, and fifty-fifty contributors to ethnic tensions.20Looting and raids (due east.chiliad., when protesters attacked NGO facilities in Maban County in July 201821) tin result in the loss of millions of dollars in humanitarian help, which non but increases access costs only also ultimately affects the number of beneficiaries able to receive aid.

Finally, the financial costs to the Due south Sudanese economy are significant and long-term. It is estimated that the consequence of hunger alone on labor productivity could mean $6 billion in lost Gdp if the conflict lasts an additional 5 years. If the conflict lasts for another 20 years, the total loss to GDP could be between $122 billion and $158 billion, devastating to an economy that has already dropped from a GDP of $15 billion in 2014 to $2.9 billion in 2018.22

Despite the significant man and fiscal costs of access in South Sudan, there are things that the international community can exercise to alleviate some of these constraints.

Ending the conflict should be the elevation priority. However, in the absence of broad and sustainable peace, humanitarian aid efforts must focus on securing access. Above all, humanitarian actors must human activity with unity of purpose, bolstered by bilateral and multilateral donors and past the United nations. A united front end to advocate for greater access and backed up by credible threats of local if not national withdrawal is important and tin can be achieved in several ways. Cutting humanitarian aid funding equally a punitive measure, still, could make the security situation worse, then any word of withdrawal should consider the potential negative repercussions of doing and so.

Commencement, more and better data is needed on the costs—human and fiscal—of humanitarian access. Although some NGOs keep internal records of access-related costs and incidents, they may be reluctant to share them with perceived competitors or out of fear of local reprisal should their disclosure become public. NGOs have a credible fear of being perceived past local actors as policy instruments of governments, which limits information sharing and must exist addressed at a higher, more than institutional or donor level. NGOs should be incentivized—through assurances of confidentiality and impartiality—to share data with a credible and independent entity (e.g., UNOCHA, the Humanitarian State Team, or the South Sudan NGO Forum), which should establish—or, in the case of UNOCHA, which periodically reports admission incidents, strengthen—a common confidential reporting system and database for disruptions to humanitarian admission.23These data, which should include financial costs which are non well understood, should exist anonymized and fabricated available in raw and aggregated course to the NGO Forum and various donor agencies and implementing partners.

Second, donors (eastward.g., the U.Due south., United kingdom, and Norwegian governments, the European union, the Un, and others) should apply these data to push button for greater standardization, consistency, and transparency in fee drove, ideally administered by ane entity in the government of South Sudan. The institution of a single entity responsible for administering fees and collecting payment (as achieved in Sudan during the early years of the conflict in Darfur) would found a major advance in alleviating humanitarian access constraints, peculiarly if codified into police force via legislation.24 A credible diplomatic official (due east.k., the U.S. Ambassador or the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-Full general) should establish a continuing meeting with the vice president responsible for the single entity charged with fee administration, relying not merely on the stated policies of the government but informed by the experiences of humanitarian aid organizations, as presented during multi-donor coordination meetings.25The meetings with loftier-ranking government officials would elevate the humanitarian admission issues—both aggregate and specific—faced past help groups, present a unified set of demands backed by apparent threats of withdrawal from certain areas or the entire country should reported access challenges remain, and talk over any proposed modifications to standardized fees once they are established.

3rd, NGOs operating outside Juba must coordinate closely with 1 another at the sub-national level, especially when sharing access challenges. A collective approach should be as local equally possible but as national or international as necessary, supported strongly by all donors to avoid diversion of funds to merely those NGOs not facing access constraints. Although they should document access challenges via the primal system discussed above, these groups also should coordinate with i another and present a united forepart to local actors over which the central regime in Juba may or may non have control. If that does not piece of work, this united front should then elevate concerns to national or international levels, supported by NGO leaders and donors. If these local, national, or international interventions do not alleviate admission constraints, the NGOs should consider the possibility of bodily withdrawal from a territory.

Although a united front—backed by credible threats of withdrawal—might non be the best fashion to resolve the political conflict, information technology is arguably the almost important and achievable approach to humanitarian access challenges in South Sudan. Other tools worth further exploration include:

- More flexible funding that reflects the dynamic nature of conflict in South Sudan, which results in regularly shifting territorial control and front lines of disharmonize;

- Surgical, tactical, and multilateral sanctions or embargoes against high- level political actors and entities that regularly and egregiously impede humanitarian access and robust oversight to reinforce these actions.;

- Consultations with humanitarian actors and South Sudanese experts (e.g., the South Sudan Enquiry Network26) in diplomatic and political efforts to end the conflict. The master purpose of the consultations would be to clarify these efforts from the perspective of their potential effect on humanitarian admission, and to ensure that all actors remain focused on upholding established humanitarian principles;27

- Funding for the joint training of NGO personnel— potentially through the NGO Forum—in principles of humanitarian diplomacy and front end-line access negotiation.

It is worth mentioning that the crisis in Southward Sudan is man-made and primarily political and astute humanitarian needs will remain unless at that place is political reconciliation. That however, will be hard and complicated to reach; reconciliation may crave changes in leadership, is laden with historical baggage, and is prone to fake promises of peace. Although a peace agreement was signed in September 2018 between President Salva Kiir and the quondam vice president and rebel leader Riek Machar, this is the 12th such understanding since 2013. There is cautious optimism that this latest peace agreement will succeed where the others have failed, primarily considering of the deep involvement of neighboring Sudan and Uganda and the return of Machar to Juba for the first fourth dimension since 2016. Peace, however shaky, also presents an opportunity for reengagement past the United States and other actors. Humanitarian admission should be at the top of their renewed agendas, especially since celebratory speeches in Juba past Kiir and Machar in late Oct referred to the importance of free, unhindered humanitarian access.28Humanitarian help—especially efforts to promote peace and social cohesion, address food insecurity and nutritional needs, and restore livelihoods—is disquisitional merely ultimately tactical and thus should not be seen as a solution to the primarily political issues underlying the conflict in South Sudan.29Such aid must be coupled with diplomatic and political pressure to sustainably end the underlying man-fabricated conflict that is the ultimate cause of the humanitarian crisis.

Ultimately, all aid efforts in South Sudan should focus on better humanitarian outcomes for the South Sudanese people. Doing so is complicated and fraught with political and structural barriers to access. Humanitarian assist is regularly manipulated for political purposes by local actors in South Sudan and aid organizations must be careful that their deportment exercise not exacerbate tensions or conflict. Aggregating their knowledge from the field, uniting backside a common purpose, and elevating that purpose to political and diplomatic levels is disquisitional to ensuring that those on the front lines have the ability to admission the places that demand it the well-nigh.

Erol K. Yayboke is deputy director and senior fellow with the Project on Prosperity and Evolution at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C

The writer would like to thank Janhavi Apte, Carmen Gallego, John Goodrick, and Aaron Milner for their inquiry back up and Dr. Luka Kuol and others for their review and suggestions.

CSIS Briefsare produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its inquiry is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not accept specific policy positions. Appropriately, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(southward).

© 2018 by the Eye for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

1United nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), "Republic of South Sudan 2018 (Humanitarian Response Plan)," Financial Tracking Service, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/646/summary; UNOCHA, "Filtered totals, Source: The states of America, Government of – Democracy of Due south Sudan 2018 (Humanitarian Response Plan)," Financial Tracking Service, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/646/flows?order=directional_property&sort=asc&f%5B0%5D=sourceOrganizationIdName%3A%222933%3AUnited%20States%20of%20America%2C%20Government%20of%22

twoIbid; United states Agency for International Evolution (USAID), "U.S. Foreign Assistance by State – South Sudan," https://explorer.usaid.gov/cd/SSD?fiscal_year=2018&mensurate=Disbursements.

iiiUNOCHA, "2017 South Sudan Humanitarian Response in Review," 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resource/2017_South%20Sudan_Humanitarian%20Response%20in%20Review.pdf.

ivThe almost contempo efforts resulted in a peace understanding signed by President Salva Kiir and leader of the opposition armed forces, Riek Machar, in September 2018. Multiple reports of renewed violence surfaced before long thereafter, and one key informant told the author that the peace agreement essentially was "an oil agreement wrapped in a peace agreement". See: Francesca Mold, "Bitter foes reunite to sign revitalized peace agreement to end civil war in South Sudan," UN Mission in South Sudan, September 13, 2018, https://unmiss.unmissions.org/bitter-foes-reunite-sign-revitalized-peace-agreement-terminate-civil-war-south-sudan; Tom Wilson, "S Sudan's latest peace deal faces early on examination," Financial Times, September fifteen, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/c78908d0-b83d-11e8-bbc3-ccd7de085ffe.

5UNOCHA, "2018 Humanitarian Response Plan," Dec 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SS_2018_HumanitarianResponsePlan.pdf; USAID, "S Sudan – Crisis Fact Sheet #11," USAID, September seven, 2018, https://world wide web.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/south_sudan_cr_fs11_09-07-2018.pdf.

viHealth in Humanitarian Crises Centre, "Southward Sudan: Estimates of crisis-owing bloodshed," September 2018, https://crises.lshtm.air-conditioning.uk/2018/09/26/south-sudan-ii/

viiUNOCHA, "Due south Sudan – Humanitarian Response Plan: Funding Update," https://www.unocha.org/south-sudan.

8White Firm, "Statement from the Press Secretary on the Civil War in South Sudan," Us Government, May 8, 2018, https://world wide web.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-press-secretary-civil-war-south-sudan/.

nineUNOCHA, "South Sudan: Operational Presence (3W: Who does What, Where)," June 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SS_20180822_3WOP_County_Level_June_Final.pdf.

10Assist Worker Security Database, "Aid Worker Security Report: Figures at a glance 2018," Humanitarian Outcomes, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resource/awsr_figures_2018_1%twenty%281%29.pdf; ACAPS, "South Sudan Crisis Analysis," https://www.acaps.org/country/south-sudan/crisis-analysis.

11Ibid.

12UNOCHA, "South Sudan: Humanitarian Access Severity Overview (September 2018)," 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SS_20180914_Humanitarian_Access_Severity_Overview_Final.pdf.

13Ibid.

14ACAPS, "S Sudan Crisis Analysis."

fifteenUNOCHA, "South Sudan: Humanitarian Admission Severity Overview (September 2018)."

16A key NGO informant in Juba told the author in October 2018 that a recent "fee" was to be a 1-fourth dimension "registration" of $100 per satellite phone. With tens of thousands of satellite phones across the country, such fees could generate significant acquirement for the levying body although almost certainly at the expense of humanitarian aid to beneficiaries.

17Cardinal informant interview.

eighteenIbid.

nineteenOverseas Security Informational Council, "Southward Sudan 2017 Crime & Safety Report," Bureau of Diplomatic Security, Usa Section of State, May 2017, https://world wide web.osac.gov/Pages/ContentReportDetails.aspx?cid=21796.

xxOxfam GB, Christian Aid, CAFOD and Trócaire in Partnership, and Tearfund, "Missed Out: The role of local actors in the humanitarian response in the South Sudan conflict," Oxfam, April 2016, https://world wide web.oxfam.org/sites/world wide web.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/rr-missed-out-humanitarian-response-south-sudan-280416-en.pdf.

21"South Sudanese rioters assault help groups in Maban," Sudan Tribune, July 24, 2018, http://world wide web.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article65913.

22Frontier Economic science, Centre for Peace and Development Studies, and Center for Conflict Resolution, "South Sudan: The Cost of War. An estimation of the economic and financial costs of ongoing conflict," Frontier Economic science, January 2015, http://www.oxfam.org.hk/filemgr/2784/s-sudan-price-state of war.pdf; Globe Bank Data, "Due south Sudan" (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018), https://data.worldbank.org/country/s-sudan.

23South Sudan NGO Forum, http://southsudanngoforum.org/; UNOCHA, "South Sudan: Humanitarian Access Review (January – June 2018)," August 15, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SS_20180817_Access_Snapshot_January-June_2018_Final_Published.pdf; UNOCHA, "Bureaucratic Access Impediments to Humanitarian Operations in South Sudan," June 2017, http://docs.southsudanngoforum.org/sites/default/files/2017-11/SBureaucratic_Access_Impediments_Survey_Report.pdf.

24UNOCHA, "Bureaucratic Access Impediments."

25"On November 9 [2017], President Salva Kiir issued a decree ordering all parties to the conflict to ensure gratuitous and unimpeded movement for NGOs and humanitarian convoys throughout the state. According to the decree, the Regime of the Republic of South Sudan (GoRSS) will agree accountable any private or group who seizes informal payments from relief convoys or otherwise obstructs the commitment of humanitarian assistance, with both national and local officials expected to facilitate emergency relief efforts. Despite the presidential decree, humanitarian actors written report that bureaucratic impediments proceed to hinder relief operations across the country. For example, one NGO recently suspended emergency Wash activities in Unity afterward local regime interfered in the organization's recruitment procedures. The pause of activities affected service delivery for an estimated 51,000 people in Unity's Bentiu and Rubkona towns, the UN reports. Meet: USAID, "South Sudan Complex Emergency Fact Canvas #2 FY18," December v, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/crisis/south-sudan/fy18/fs2.

26London School of Economics and Political Scientific discipline, "Workshop Report Conflict Research Programme - 2018 Almanac Research Workshop", http://www.lse.air-conditioning.britain/international-evolution/Avails/Documents/ccs-enquiry-unit/Conflict-Enquiry-Programme/crp-workshop-reports/CRP-Annual-Workshop-2018-Report-Final0208.pdf

27UNOCHA, "OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles," July 2012, https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June12.pdf.

28"Due south Sudan celebrates new peace accord amid joy – and skepticism", The Guardian, October 31, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/october/31/south-sudan-celebrates-new-peace-accord-amid-joy-and-scepticism

29Faustine Wabwire, "The Confront of Dearth in South Sudan: A Call to Bridge the Humanitarian-Evolution-Diplomacy Split up," Breadstuff for the World Found, April 2018, http://www.bread.org/library/face-famine-south-sudan-telephone call-bridge-humanitarian-evolution-diplomacy-split.

Source: https://www.csis.org/analysis/accessing-south-sudan-humanitarian-aid-time-crisis

0 Response to "Us Will Review All the Humanitarain Aid to South Sudan White House"

Post a Comment